My maternal grandmother was born in a town called Codo, just 27.2 kilometers away of the birthplace of Francisco de Goya y Lucientes, in Fuendetodos, century something after his death. It seems long time, but perhaps between my grandmother and Goya may have only a few two or three generations of difference. Thinking about all this makes me feel Goya not too distant.

My maternal grandmother was born in a town called Codo, just 27.2 kilometers away of the birthplace of Francisco de Goya y Lucientes, in Fuendetodos, century something after his death. It seems long time, but perhaps between my grandmother and Goya may have only a few two or three generations of difference. Thinking about all this makes me feel Goya not too distant.

Along with my activity as a painter, my professional life runs between art and the Bioneuroemotion.

Bioneuroemotion® is a scientific method in which we study the condition of emotions in people’s lives. We study our personal unconscious, the familiar and social-collective unconscious. We studied how all this affects our mind, our psyche, and in resonance, our body and our experiences.

More than as an artist, I would like to give a personal view of Goya from my professional activity of companion in Bioneuroemotion. As a painter, what I can say is that Goya wonders me for his genius. I have closely observed their plates in the National Chalcography in Madrid, they are impressive. You can see the strength of the artist hand on the metal. This excites me. Even I could see his paintings on the walls of the Charterhouse in Aula Dei (near Zaragoza). I have also seen several of his works in different museums. From all this which captivate me are his black paintings exhibited in the Prado Museum.

Detail of the black paintings.

I see in the work of Goya the emotional impacts of human barbarism. With their images and transcriptions of the reality of his time, touch me the experiences of that time population. I think about it, and there is a knot in my stomach. How is the human race! If I think a bit, perhaps what touch me most is that we have not changed much since then; the truth is that there are not too many generations of difference. We continue in a same dynamics. We are inheriting generation after generation this barbarism, and men and women fail to end with the traumatic and painful experiences.

Goya makes conscious the unconscious for a time. It brings to light the human shadow. Does it present to the eye of the observer. It seems that makes use of a kind of pictorial surrealism, but nothing is further from it. Put in relief the reality of the Spain of the time. He paints with extreme realism, or rather hyper-realism, the heavy darkness of the collective unconscious –a term coined by the Swiss psychiatrist Carl Gustav Jung, who postulated the existence of a substratum common to human beings of all times and places in the world, consisting of primitive symbols that expressed a content of the psyche that is beyond reason-.

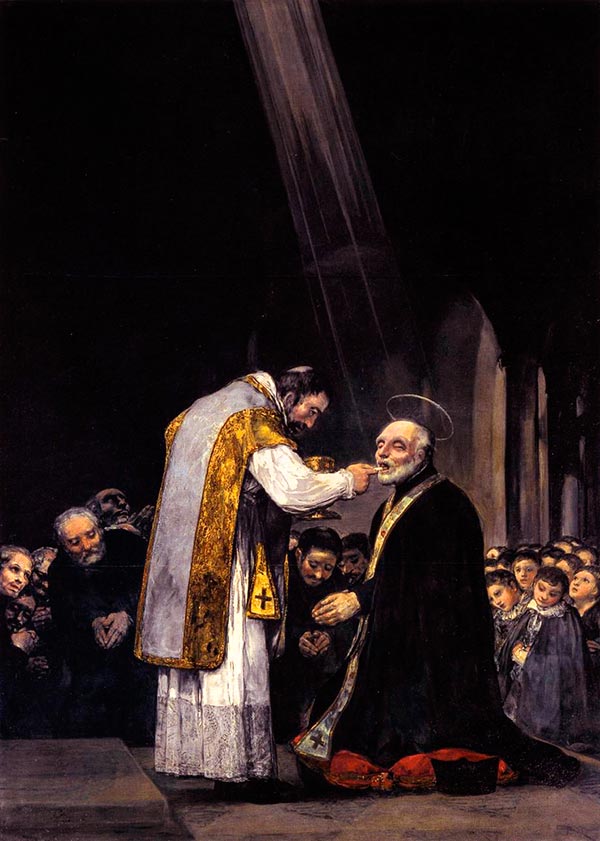

In his portraits, Goya shows with great courtesy personal attitudes and emotions of who poses for him. His palette and his brushes expressed through a skilful hand, being in essence. Product of his high degree of observation summarizes with several strokes the soul of the person. His way to observe is no longer an art so or more sublime than the art of his hand.

Goya absorbs in his physicality and his psyche what has in front of his eyes. He makes a sort of “emetic act” with brush and paint. He sees what the eye cannot see, express and translates it in spot-coloured.

Faith to this is his black paintings. He made them after visiting mental hospitals, cemeteries and extreme penitence and charity hospitals. Here it highlights the shadow of man and woman in an absolute realism, even the shadow of the collective of the country itself. Absorbed and translated with painting, what remain hidden, what is not said, the sin, drowning and contempt for brother to brother. Monsters of a reason dream with no reason.

Let’s not also forget his etchings, Disasters of War: atrocities made and lived by men and women. Perhaps Goya, if had not been able to express -talk- with his engravings and paintings, what his eyes saw, the reality of his life had led him to the more intense insanity. His vital rage is expressed in the power of the strokes on metal plates of the engravings. I imagine that his deafness was their unconscious biological resource to be able to withstand so much suffering. He did turn a deaf ear to violence, to the unreasonably, to the worst that human beings can be expressed in the physical world. It can also do dent in him the indifference of the nobility towards their fellow human beings. It would not surprise me that he could check firsthand that indifference of a few “noble” men and women towards other men and women who only separated them by the social ladder; a stupidity of castes that mankind invented I don’t know when. Another outrage.

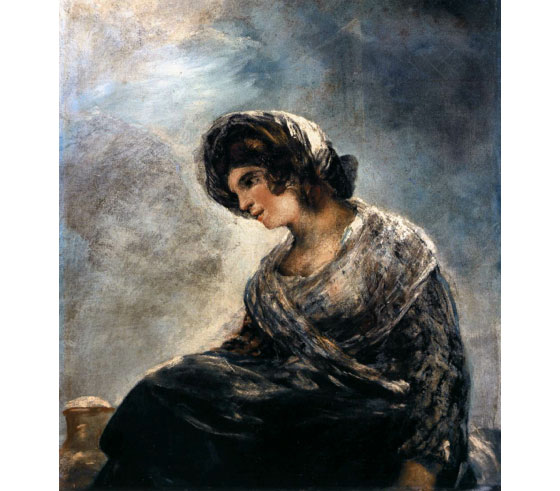

In the end, his departure from Spain to France seems that relieved the shadow that could haunt his mind and psyche. You just have to appreciate the change in his painting, more manageable, softer and looser, as for example in the painting ‘La lechera de Burdeos’ (The milkmaid of Bordeaux).

In my personal hallucination about Goya, I see a man endowed with high abilities for art and psychology; a great ingenuity to capture deep in people. He is a man sensitive to the human.

Following my hallucination, I think intuit in his way to observe, a psychoanalytic capacity out of the ordinary. He tuned, like an antenna, with the human shadow. He translated with extreme reality the hidden, unseen in the minds of the unconscious. The beauty too.

I close my eyes, and those monsters of reason dream appear and become real today. Release the inherited shadow; release a reason with no reason.

Perhaps the release may look that is very far from the essence of the heart, which is love. I dare say that it is not so far. There is hope. While there is a heart that pumps, there is a glimmer of hope that illuminates our conscience with the essence of what we are and we have never ceased to be, despite the barbarity of the ego.

I want to thank Don Francisco for his both human and artistic legacy. For his bravery and courage, his sincerity in showing what very few dare to show: the monsters of the outrage.

Eduardo Cebollada