In regard with the drawing, the artistic background of the RAESFC has a very large set since the Drawing School founded by the Society will be the immediate forerunner of the Royal Academy of Fine Arts of San Luis.

Pablo Jiménez says that in the Italian Renaissance drawing was something prior to art, although in its process: before the painting, before the sculpture, before the architecture, it was drawing. And it belonged to the workshop, to the place where dreams take a shape. From the technical point of view and the adequate conservation, its fragility and extreme sensitivity (to moisture, as much or even more than) to the light, requires severe and continuous care. Reason why is well known that they should be stored without frame, horizontally and in the dark.

But it is not easy to define or describe what a drawing is. As we said before when it is created, it comes from the first and initial idea. José Manuel Matilla, head of Department of Drawings and Prints of the Prado Museum says that Goya “constitutes an exception in Spain. There was nothing like him before, and for a long time, since then”. And in regard to his technique, adds that “Goya corrected rarely. Since the beginning had it clear. Only included nuances, a few changes.”

It will be a year later when finishes the job of first approach, and cataloguing and public display of the funds of the Economic Society. Indeed on October 17th 1983 and to December 10th of that same year we present the exhibition Drawings of Academy in the Congress Centre of the Bank (Patio de la Infanta named today). They are offered to the public in general a set of 101 pieces, editing a third catalogue, this one with 108 pages, 121 reproductions, among which only one, the possible nude self-portrait of Goya, is in colour. Once again with text and cataloguing by Gonzalo de Diego, dossiers and biographies in charge of the same by Gonzalo de Diego and José I. Pascual de Quinto.

It will be led later to the city of Valencia, constituting the opening exhibition for the new Exhibition Hall of the Bank in that city. It was inaugurated on December 22nd and ends on January 21st 1984. An exceptional reception took place in that city – not in vain Goya was also academic of San Carlos- and thousands of visitors celebrating such a singular way of inaugurating a new cultural centre.

So those exhibitions are compiled into a global catalogue that, sum of the three released, within its modest limits represent 254 pages (66, 80 and 108), with 323 illustrations (85, 117 and 121) of which 7 in colour, confirming the initial idea of a very measured cost and even rigorous in some cases. 309 were the exposed pieces. The objective had been reached so that the own Bank considered adequate and the Economic Society was duly confirmed. To the point that I personally assumed, in addition to the enormous moral satisfaction to them and the great honour of such a work put at its service, my appointment as a resident member in the Royal Society Aragonese of Friends of the Country at the meeting held on March 3rd 1982.

But returning to Drawings of the Academy it should be recalled here that the exhibition catalogued and publicly presented two drawings by Goya of outstanding quality and importance:

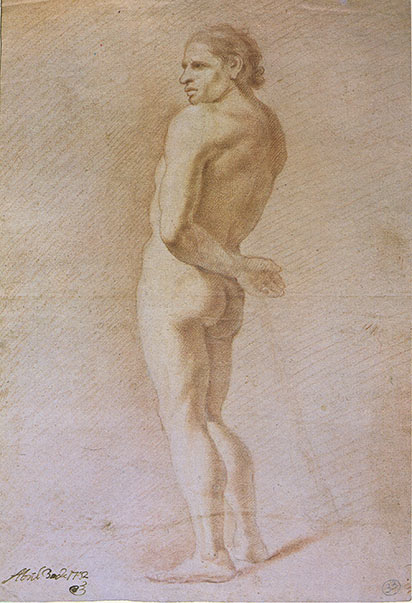

(Likely) Self-portrait of Francisco de Goya y Lucientes. Drawing in sanguine and white chalk on a previous sketch in pencil graphite on white laid paper. 518 x 352 mm, circa 1785-90. On the reverse there is another drawing, to the sanguine. The inscriptions “April 30th 1792″ and a flourish, both characteristics of Goya and authentic, were certified by Dr. Canellas, Professor of Palaeography and Diplomatic and author of Francisco de Goya, El Diplomatario. Drawing was listed with the number #59.

(Probable) Autorretrato de Francisco de Goya y Lucientes.

Dibujo a sanguina y tiza blanca sobre un boceto previo en lápiz grafito, sobre papel verjurado blanco. 518 x 352 mm, Francisco de Goya.

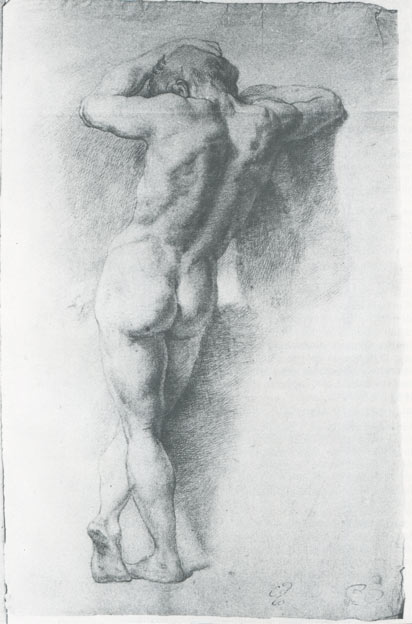

Manly bare foot and back. It is a copy of an original drawing by Pompeyo Batoni which also appeared in the same exhibition with catalogue number #31.

This drawing, copied by Goya, is made in point lead on laid paper, prepared and dyed in gray. Unlike the model of Batoni whose paper is dyed in blue. 522 x 332 mm. (Batoni model measures 531 x 400 mm). Performed by Goya circa 1776 to 1790. Bottom right, two signs; the left belongs to Don Diego de Torres, Secretary of the RAESFC from 1776 to 1809(?). The second, by Francisco de Goya, listed with the number #60.

Desnudo viril de pie y de espaldas. Copia del original de Pompeyo Batoni.

Punta de plomo sobre papel verjurado, preparado y teñido a gris 522 x 332 mm. Francisco de Goya.

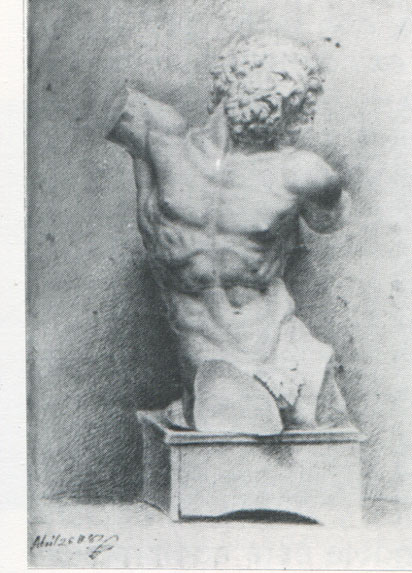

Laocoön (copy of the plaster). Drawing on tip of lead on white laid paper with watermark “J. Honig & Zoonen”. 482 x 344 mm. In the cataloguing and public exhibition of 1983-1984, it was listed as a possible Spanish anonymous from the second half of the 18th century (Francisco de Goya?). It has a possible unreadable inscription at the top right corner. And in the bottom left corner it says “April 26th ‘82″ and signature. All inscriptions and signatures correspond to Francisco de Goya, according to opinion of Doctor Cañellas. Doña Manuela Mena said in its review prior to the exhibition that most likely was an original by Goya (See article on this blog dedicated to Eleanor Axon Sayre in Zaragoza, published on July 2nd 2013).

Laocoonte (copia del yeso)

Dibujo en punta de plomo sobre papel verjurado blanco. 482 x 344 mm. ¿Francisco de Goya?

The blog of Realgoya, publishing these articles and testimonies about the artistic activity of last few years, aims to contribute to the better dissemination of the figure and the work of Francisco de Goya and, on this occasion, open doors of the Economic Society and its heritage to the digital world, allowing many people who do not have access to these collections may enjoy the valuable benefits offered, and not only for residents in Zaragoza and Spain, but in the wide world of the Internet. And in any case, keep his memory alive and accessible for all.

Let’s look now at the other reason that concerns us: announced exhibition on the Royal Society Economic Aragon to be inaugurated “around April 23rd“, in fact, as María Teresa Fernández says, “…its heritage and history are also poorly known” and, as mention the curator of the exhibition, Domingo Buesa, “the funds that holds the institution are very unknown to the general public”. Not in vain have passed more than 30 years since those first exhibitions that we have been relating, and clearly it has arrive the time to close this chapter in the best possible way.

“So much of art has never spoken and has never felt less than now” Anselm Feuerbach sorrowed in 1882. He expressed this way a discomfort that had begun to be felt in the second half of the 18th century, with considerable impulse of academic exhibitions. The art began to become a public affair and with it appeared the figure of the critic. But concurrence blurs the look, as reveal Emilio Zola in his criticism to the Parisian salons in 1866. If only medal winners, i.e. those who are already enshrined, make up juries, demand Zola, what protection those who still have no medal to defend themselves will benefit then? Amateurs will precisely be who deal with doing so and since then artists will seek the general public hoping to find in it a positive judgment.

In 1763 Diderot hymned the public exhibition as being, above all, an institution seeking “to all stages of the society, and in particular men of taste, a useful impulse and a pleasant recreation”. Always the compulsion to representation of the State, the monarchy, the individual, has been an important invitation to be surrounded by art works. The diffusion of the Academies in the 18th century owes much to the pride of the courts seeking to be dazzled by the splendour of art. Napoleon was receiving ambassadors and foreign diplomats among the artistic collections of the Louvre, in order to show them, almost in contact with the acquired works in his conquests, the unity of Europe under the domination of France. Power is served of the art exhibition as a mean of giving abroad a representation of their aspirations and their models, its policy and identity.

In such a way that exhibitions have acquired a political status, they form part of the privileged means by which document and illustrate the agreement, the alliance and international cooperation, the national and regional identity, historical continuity, self-awareness and love to the culture of a State. For this reason and despite the tremendous actual economic crisis, are still justifiable such displays. Thus, since its origins, exhibitions have experienced the discrepancy between what their visitors expect from them and what they were proposing, or intended to propose. Perfectly aware of its prerogatives and its new responsibility, the growing bourgeoisie of some European countries in the 19th century will assume, certainly with natural and amazing efficiency, the patronage of artists replacing the role that until then had first played the Church and then the Palace.

(To be continued…)

Gonzalo de Diego