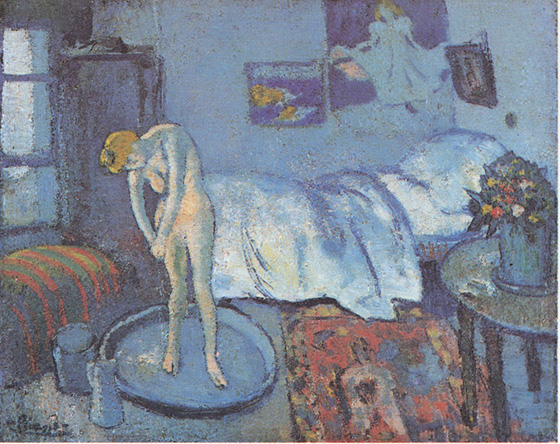

At 1600 of 21st Street in Washington, a beautiful hotel in red brick houses, in the former family residence, the artistic collection of Marjorie and Duncan Phillips. It is the central office of what is known as the Phillips Collection, excellent museum and collection world-wide known. Within its eighty and many best-known masterpieces include pieces of El Greco (Saint Peter Penitent) or Goya (with same title of Saint Peter Penitent). The museum also displays other wonders as one hand-out by Picasso (The Blue Room). It is an oil-on-canvas of 50.6 x 61.6 cm. acquired by the Phillips in 1927.

The Blue Room Pablo Picasso, 1901 Oil on canvas. 50,6 x 61,6 cm Phillips Collection. Washington

This picture, painted by Picasso in his studio of the Parisian Boulevard of Clichy at the end of 1901, is also inspired by a pastel from same collection (the Degas After the Bath), and hides beneath a previous painting as we have been able to know a few days ago. The Picasso’s Blue Room represents an amalgam of styles and artistic elements, and lays in it the presence of a Picasso who, as surreptitious voyeur, watches his model, as canonically does Degas with his in After the Bath. A topic to which Picasso will return again and again throughout his life.

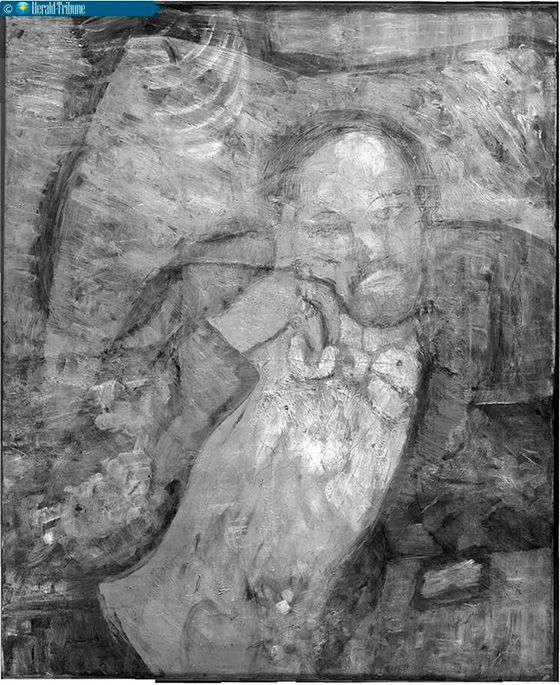

Unknown person hidden under paint “The Blue Room”

As reported on last 17th June from Washington Brett Zongker, from Associated Press, scientists and art experts have found this painting hidden beneath one of the first masterpieces of Pablo Picasso, The Blue Room, using the latest advances in infrared images that reveal the portrait of a man with the face resting on his hand, with jacket and tie and three rings on his fingers. The question now is to know who is this? At the moment is a mystery. It is known that it is a painting at the beginning of Picasso career, in Paris, at the beginning of his blue period, characterized by melancholy themes. And over the past five years, experts from the Phillips Collection, the National Gallery of Art, from the Cornell University and the Delawares Winterthur Museum have come to develop a clearer image of this mysterious person hidden beneath the surface of the painting. This way the curator at the Phillips, Patricia Favero, has been working with other experts to analyze the paint with multispectral image and x-ray fluorescence scanning technology, to try to identify the colours of the hidden painting. Now research continues, in the midst of an almost detective-like operation, while the painting is doing a roaming by South Korea until the beginning of 2015. It’s a serious question, reasonable and well posed, and subjected to a rigorous research.

Another very different thing is what has come to light recently regarding the purchase of a Goya dated in 1783 by the Aragon regional government (DGA) in Spain and the first financial institution in the region (Ibercaja), who at the end of 2006, lovingly purchased together the portrait of Don Luis María de Borbón y Vallabriga. A portrait that hides something that is not, by the way, another painting. What remains hidden to the taxpayer is to find out why a painting whose market value was not exceeding by far the two million Euros was purchased by five times more, i.e., ten million Euros. What is the last reason for such nonsense? While it is true that “the fool confuse value and price“, it is just worth to minimally analyze a purchase as spectral as incomprehensible to the common people, to begin to ask questions in a torrential way: this has been a unique performance because, as far as it is known, had no continuity, or had it? Is, therefore, any planning? If not, as it seems, for what is truly shown this behaviour? We handle so much money that there is a need to do something that justifies it? Is it that? And, suddenly, someone “thinks” as we are in the land of Goya… Let’s use Goya -once again- to let see that we do something, that the name of Goya always decorates much and calms down the people. It is not though a hidden portrait, as in the Picasso one, but it is a portrait that hides something. It hides that a Foundation, PLAZA (Zaragoza Logistics Platform), funded by the Board of Directors of that logistics platform (sic) have enough money, a lot, perfectly willing to be spent in a way as illogical as hasty, to the extent that the Association of Public Action in Defense of the Aragonese Heritage (APUDEPA) filed a complaint at the prosecutor’s office for “an alleged crime of misappropriation of public funds”. To this purchase the mentioned PLAZA Foundation includes it then, euphemistically, in the in vogue “corporate social responsibility” project. Funny, isn’t it? It was said already by Goya himself that “in remembering me Zaragoza, I burn alive”. Well, two and a half centuries after things have not changed that much.

Don Luis María de Borbón y Vallabriga Oil on canvas. 130 x 116 cm. Francisco de Goya, 1783

In case the wrong trained administrators responsible (?) for such foundation use this way money that is not theirs will have to agree that altruism, as defined by the RAE (Royal Spanish Academy), consists on “diligence in the good of others even at the expense of our own”, is a chimera for these people. Of course they are anything else but altruistic, what blush every decent citizen. Because this kind of customs and traditions, currently and fortunately under the watchful and vigilant eye of Justice, no doubt supposed irresponsibility, excessive personal ambition and lack of sense in an State and few sectors unfortunately used to privileged treatment. But today in Spain, and to its effects we refer, citizens are in hands of idolaters of the money that have put it in the centre of their lives. And thus it is understood much better that if in the Shanghai Ranking, the most prestigious in the world in the classification of the top 500 universities, it has to go down to rank 200 to find a Spanish one, Universidad Autónoma Madrid; among the first 400 there are only five Spanish, but unfortunately the university in the land of Goya is not among those 400. It is not surprising, therefore, the lack of social responsibility and the absence of moral criteria of a ruling class (!) in a society is tricked with this naturally, and refuses to give systematically all sorts of explanation.

The painting to which we refer is a complacent portrait but mannered, cloying, soft and lack of brightness, and perhaps is exceeding for unnecessary, to increase the payroll of Goyas in the hometown of Goya, Zaragoza, which already boasts magnificent examples of portraits, such as that of Duque de San Carlos (Canal Imperial de Aragón) and that of Don Félix de Azara (Ibercaja). While it is true that portrayed don Luis María de Borbón y Vallabriga is a son of the zaragozanian María Teresa de Vallabriga, who was the wife of Infante don Luis de Borbón and that would be a cardinal of the Catholic Church, and in such a condition portrayed brilliantly, this time even by a more mature Goya. This is not, ultimately, a paint even necessary in Aragon; There were, and are, others best in quality and significance, and that could have been purchased for a lot less money. There is no doubt of this. But arranged this way the issue enters the mechanics of this very particular kind of patronage: commercial agents appear and although some deny it, the sponsorship development involves the creation of a sort of “market” with an offer and a demand. Usually, bidders and applicants prefer to contact directly, without any kind of interference. Hide. Should be this the case, in which neither seems that they have intervened on the shopper hand true experts in the work of Goya, in their market prices nor in the realization of this major purchasing, so we could conclude that everything points to a failed act, conspicuously hidden and more than worthy to be clarified.

What can we do, simple witness that look, with eyes of hen, a shattered Spain and that where the slowness of our Justice is always late? Although it comes. We always have the comfort to remind our elders, our masters and the dignified and decent people, a lot, which have been and still remains in Spain:

Professor Julián Gállego in his excellent book El Pintor de Artesano a Artista (University of Granada, Spain, 1976) illustrates on the nobility and ingenuity of paint and offers some of the varied ways to show a picture and, even, concealment and other surreptitious visions of painting. On the other hand, Professor Gállego also cites to Palomino in his treatise on the theoretical and the “practice” of the painting (1715), which in a wonderful outburst ensures that “not writing for men and learned scholars, who know (paint) and extol it, nor for the heroic princes and knights, which illustrate, honour and sponsor it; as for the first it would be offense assume them lukewarm in the knowledge of a truth such constant, and for the others would be tort persuade them of a clear course: but for a true, indiscreet masses that taking by outrage know something, make reason of State ignore it all; upholstered in a fantastic cavalry, forging of ignorance, leisure, and vice the coats of arms of the nobility. Rare lineage of barbarians! Swollen with the pride of a vain prosperity, being dumb argument of a blind fortune and tacit rebuke of an unfair fate, looking with contempt to the architects and scholars, full of science and experience, men without having them more ornament that read wrong and write worse: but for them in vain is to dispute it; because even they have to read it, nor its approval has to illustrate it, as nor his contempt folding them down…”

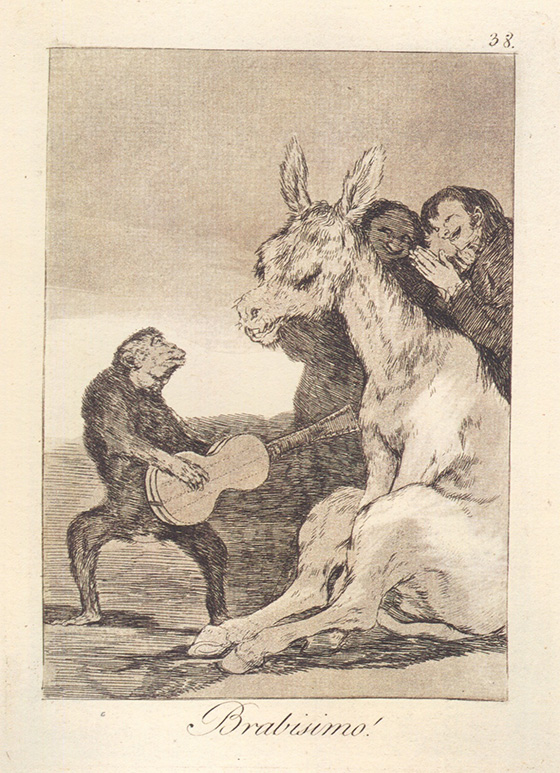

Thus, the question is as old as the world is and Goya also illustrates it in the capricho 38 Brabísimo!, in which proclaims there are patronages provided only by fatuity.

38. Brabísimo! Aguafuerte, aguatinta bruñida y punta seca. 219 x 152 mm

If finally we consider a painting as something tangible, and not only that but also as something intangible, it deserves of it an extraordinary respect and cannot or should not be altered or damaged, as exemplary shows the Phillips Collection. Notwithstanding the foregoing, we want to be charitable and so remember to finish the illustrated Jovellanos, who wondered in his Praise of the Fine Arts:

“Who is this, they say, that from the forum is coming to consecrate his sterile and scruffy eloquence to an object so new for him and pilgrim? And, the truth, sirs, what does in common between serious and profound studies of a magistrate and the sublime and delicate fine arts knowledge?”

Gonzalo de Diego

Leave a Reply