The fable, short story in verse or in prose to illustrate a precept, is all a literary genre whose characteristics would be defined and profiled by the Greeks, people which, in the opinion of H. Taine, have thought that much, have its spirit so well done, that their guesses have been found many times with the truth. However the origin of the fable goes back to Mesopotamian fables arrived in Greece around 2,500 b.C. and later in India. Both routes, Greco-Roman and Indian, constitute traditions that will subsequently contact the middle ages through Arab translations.

While Aesop passes as the promoter of the first collection of fables, has not reached us nothing of him -even his existence is controversial- and we know his fables by subsequent collections. In any case Aesop, whom tradition attributes the condition of slave of Phrygian origin, is known author since long time ago and is the first model known and reported. (Julián Gállego says that) was first a slave, then freed and dead by the residents of Delphi. Herodotus places his life between 570-526 b.C. and Aristophanes quotes him as a usual reference in his comedies.

Fictitious and allegorical nature, the fable is a resource of speakers to achieve persuasion and not intend to both provide an unreal incident and not credible, usually in the animal world, as show it to us by what this event means in way of meditation about men’s world. Sandwiched between genres as comedy, as opposed to the epic literature, for example, with the pass of time the fable, by its format and its easy, its high moralizing and persuasive value will serve the different philosophical schools -stoical, cynical- for the education of young people, due to its high moralizing and persuasive value. In any case, Aesop’s fables are characterized by brevity and simplicity and will be used, along with the Phaedrus ones, in education within a moral lay that essentially aims to emphasize vigilant attitude towards life.

Thus Phaedrus, in the 1st century, speaks of teaching to delight:

Duplex libelli dos est: quod risum mouet

et quod prudenti uitam consilio monet

So that they will be presented to fulfilling perfectly the Horacian utile dulci maxim, as testifies the Latin grammarian and rhetorician Quintiliano (1st century), and already in the European middle ages, shows a pleased Petrarca when remembering his early school experiences.

For F. Rodríguez Adrados, in fables “the mighty is imposed, are any of the reasons for the weak (…) But the weak may be superior in wit and succeed with deception or cunning. And there is criticism and mockery of vanity, stupidity, greed.” According to this thesis, is best understood why fable awakens more or less interest in certain historical periods and groups such as the cynics in the classical Greece, and, as we will see ahead, the enlightened and liberal Spanish of the 18th and 19th centuries. Especially taking into account that the fable, for its specific characteristics, in spite of being used to designate shortly human vices and also as a method of first school indoctrination, does not necessarily have in children its best public, because in many cases will be via of profanity and cynicism and consequently much more suitable for an adult audience.

Velázquez and Aesop

“In the middle ages… collections of aesopic fables (…) were increasing gradually. Romance literature in the Iberian peninsula offers good field for this fabulous spirit, and thus can be seen, to give just an example, at the multiple apologies inserts in the book of the Good Humour by Juan Ruiz”

However, the fable as a genre had been despised, when not ignored, by literary scholars until deep into the 17th century. But it is worth remembering that Velázquez had lived in the Baroque, a period in which the art is theatrical and artificial, in which nothing was what it seemed.

According to López Rey “the use of Greek fables along the life of Velázquez, until the very end of his life, is so repeated that, whatever the part corresponding to the whim of the King was, cannot be supposed was animated primarily by a sense of irony and critical shredder, as not few times has been claimed”.

Felipe IV had gathered at the Torre de la Parada a series of great artists, agree in essence with the belief that the people of talent have never more talent than when they are together. And for this purpose, as well as Rubens with his Saturn, Vulcan, and Ganymede adorned some of the rooms, the Flemish painter Paul de Vos -brother-in-law of Snyders- also had participated in the decoration of the Torre, precisely illustrating several fables of Aesop, and proving once more that the fable, as advice or admonishment, serves both for literature and for any other artistic activity.

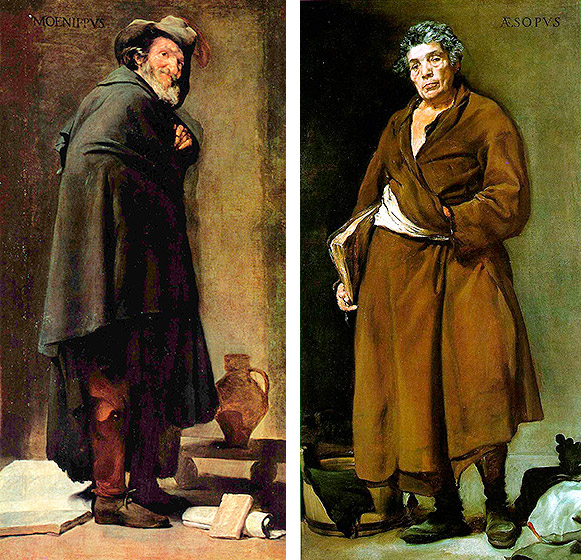

For J. Brown, it is equally possible that the Aesop and Menippus were Velázquez response to another couple of paintings by Rubens, Democritus and Heraclitus, hanging in the same building. Because in classical literature, Aesop was a place also as a critic of the Apollonian or cultivated life and not only as a storyteller. And in the context of the hunting residence at montes del Pardo, the portrait of Aesop along with the one of the cynic Menippus, at the same time exalting the wisdom and crackle of philosophical gravity of the common man, they would be as the patron saints of the simple life.

In conclusion, Julián Gállego says that seems plausible that in a leisure Pavilion –as much as hunting was a royal art prepared for the war-, was admitted a miscellaneous decoration in which satire of ancient culture, so evident in the Golden Century in literature as in painting, had a right place. Because “If Democritus, who laughs at everything, and Heraclitus, which takes everything as a cause of crying, is often provided to the Spanish satire, Aesop, who instructs humans because of their similarity with beasts, or Menippus, in his cynical position, that worth the effort”.

Menipous Diego Velázquez, 1639 – 1640 Oil on canvas 179 x 94 cm. Prado Museum, Madrid, Spain Aesop Diego Velázquez, 1639 – 1640 Oil on canvas 179 x 94 cm. Prado Museum, Madrid, Spain

The Velázquez Menippus and Aesop constitute, on the other hand, characteristic pictorial types of 17th century in which, as José de Ribera will do with his Democritus, employ venerable figures of Antiquity dressed in tattered clothes of the 17th, in order to find a clever way to summarize their themes and essential ideas.

But he (the seller) could not dress him nor present him as required, because was a kind of corpulent and completely deformed guy, so she dressed him in a burlap robe, tied a strip of fabric at the waist and placed him between two beautiful slaves

(From the biographical legend of Aesop where is putted on sale with other slaves).

- Brown ends his file of the portrait stating that no one has exceeded results that Velázquez scored when he came to this special genre. Aesop, man in advanced age and soft and tired face, carries a damaged book in one hand and introduces the other at the waist of the broad cloth that serves as a little flattering dress.

A cube with a piece of leather that hangs on the outside of the container appears on the left side of the canvas, discreet reference to the fable in which a man neighbour of a tannery just finish learning to tolerate noxious odours from leather.

In front of an imaginary affair as the one of this canvas, the brush of Velázquez back flies and conveys a sense of solid structure, but does so by dim and hazy effects of light, with an extraordinary delicacy. Facial features are achieved with very light strokes, and then the lights are irregular fragments of filling of white lead. In Aesop hair can be seen short brush strokes and paint specks that give this aspect of curled and stiff.

In conclusion, Velázquez fails finally a work of the overexcited imagination, but the lucid reason. Is built to last by itself and without help, as so cool and rightly know to capture Francisco de Goya when, long after, make wonderful cuts of the paintings of Velázquez owned by the Royal Aragonese Economic Society of Friends of the Country.

To be continued….

Gonzalo de Diego